The definitive end of the third era of additive manufacturing

3DP War Journal #57

The bankruptcy of Desktop Metal marks the symbolic end of the Third Era of Additive Manufacturing development. In my view, from now on, the industry will evolve along two separate tracks, dividing into a consumer (mass) segment and an industrial (specialized) segment.

Most likely, these segments will never converge, gradually evolving into entirely independent markets. The difference will become as vast as the one between home and office paper printers, and large-scale printing machines that operate with B1 sheets or paper rolls.

FFF technology will become its own market—a separate branch that will be connected to additive manufacturing only by name and origin.

All remaining technologies will form a distinct market based on narrow specialization in selected fields (photopolymer technologies mainly in dental, medicine, and jewelry; powder-based metal technologies in aerospace, defense, energy, and other specific areas of industrial manufacturing; powder-based polymer technologies will gradually lose significance).

What are the three eras of AM, and why did Desktop Metal play such a key role?

The Era of Rapid Prototyping (1984–2010)

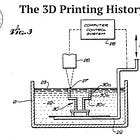

3D printing was officially born in 1984 thanks to Charles Hull. Two years later, in March 1986, after receiving the patent for stereolithography—the first additive technology—Hull co-founded 3D Systems Inc. with Raymond Freed. It was the world’s first company dedicated to manufacturing 3D printers.

Following in Hull & Freed’s footsteps were companies like DuPont with their Somos 3D printers, and Japanese firms like NTT Data CMET and Sony/D-MEC. At the same time, other inventors and entrepreneurs began to introduce alternative additive methods such as SLS, invented by Carl Deckard; FDM, invented by Scott Crump; and binder jetting, developed by a research team at MIT led by Emanuel „Ely” Sachs.

Together with European companies like Materialise and EOS, all of these pioneers laid the foundations of the global AM industry.

The common feature of all these companies, regardless of their specialization, was rapid prototyping. After all, 3D printers were originally developed for this purpose—to quickly and cheaply create prototypes. In the 1980s and 1990s, no one was considering their use for end-part production or serial manufacturing.

Limitations included both the print quality and the complex production process. 3D printers in the 1990s—despite their industrial character and price tag—lagged far behind today’s systems in terms of quality and ease of use.

Still, they made sense for prototyping, which was either done by hand or incurred enormous unit costs due to tooling and processing.

This started to change slowly in the 2000s, as photopolymer 3D printers began to be increasingly used for producing customized medical applications (e.g., parts for hearing aids), and polymer (FDM) or metal (PBF) 3D printers were used for manufacturing specific, specialized end-use parts.

But these were still incidental applications. 3D printing was synonymous with rapid prototyping.

The Era of Consumer 3D Printing (2010–2017)

In 2004, Adrian Bowyer—a British lecturer from the University of Bath—began work on a self-replicating 3D printer as part of the RepRap project. A year later, Evan Malone and Hod Lipson launched a similar project—Fab@Home—at Cornell University’s Department of Mechanical & Aerospace Engineering.

These projects laid the foundation for the emergence of desktop 3D printers, which would soon become the driving force of the entire industry.

In 2009, just after the expiration of patents on FDM technology, MakerBot Industries was founded in the U.S., and Bits From Bytes in the UK—two of the world’s first companies offering desktop-class 3D printers that were significantly cheaper than original Stratasys systems.

Following their lead came a wave of entrepreneurs who, backed by venture capital and angel investors, began creating their own companies producing similar—though not necessarily equally good—3D printers.

Thanks to the charismatic Bre Pettis—co-founder and leader of MakerBot—3D printing entered mainstream media, which began promoting 3D printers as “the next big thing” and the foundation of the next industrial revolution.

Unfortunately, the promises made by these companies weren’t reflected in reality. Although desktop 3D printers were visually appealing and relatively affordable (mainly thanks to Taiwan’s XYZPrinting), their performance fell far short of consumer expectations.

They were still relatively hard to use, prone to failure, slow (compared to user expectations), and limited (in terms of geometry, color, and accuracy).

By 2015, the great bubble of expectations began to burst. The more people bought consumer 3D printers, the more widespread the disappointment with the technology became.

Companies failed to meet their sales forecasts, posting disappointing results. Lack of profitability and mounting losses led to a wave of bankruptcies.

Around 2017, the consumer market was in retreat. Former leaders began to pivot and develop solutions for manufacturing. The desktop segment began to industrialize.

At the same time new companies emerged on the market with a completely different approach from the start.

The Era of Mass Additive Manufacturing (2017–2025)

As companies specializing in consumer 3D printing gradually declined, a new generation emerged—focused from the outset on the industrial sector.

The first was Markforged, which in 2014 introduced a 3D printing technology based on continuous carbon fiber. Although the company’s early printers were desktop-style devices, their applications and pricing clearly placed them in a higher category.

But most importantly—Markforged no longer aimed to produce prototypes, but end-use parts.

Soon after, a new wave of companies with the same mindset appeared—Carbon, Desktop Metal, Nexa3D, and Velo3D. HP entered the stage with its Multi Jet Fusion technology, while GE acquired Concept Laser and Arcam AB, and announced development of its own metal binder jetting technology.

Formlabs—one of the pioneers of consumer 3D printing in photopolymer technology—pivoted toward professional applications with the release of its third-generation printer, the Form 3, ultimately leaving the consumer market behind.

The goal of these third-wave companies was to bring 3D printing into industrial manufacturing—not just for rapid prototyping or occasional one-off parts, but for serial or at least low-volume production.

3D printing was to become a peer manufacturing method alongside CNC machining, injection molding, sheet metal cutting and bending, and casting.

Just as Bre Pettis was the face of the consumer 3D printing movement in the second era, Ric Fulop—founder and CEO of Desktop Metal—became the prophet and advocate of mass additive manufacturing.

Desktop Metal played the most pivotal role among the new generation of industrial 3D printing companies for several key reasons. Unlike its peers, Desktop Metal was not only focused on industrial production from the outset, but also carried the most ambitious vision: to replace traditional manufacturing methods with binder jetting metal 3D printing at scale.

Fulop positioned the company as a revolutionary force, garnering significant attention from investors, partners, and the media. The company’s aggressive marketing, and high-profile partnerships set the tone for the entire sector.

The peak of this movement came in 2020–2021, when companies began to go public en masse via SPAC mergers. That didn’t end well...

Ultimately, every company from this second wave fell into serious trouble. Some went bankrupt, others underwent major restructuring and are now barely staying afloat.

The only company that has survived both the second and third eras and is still doing remarkably well is Formlabs.

Overall, it became clear that just as consumer 3D printers couldn’t meet the expectations of regular end users in 2010–2017, industrial 3D printers also weren’t quite suitable for serial production.

The issue here is far more complex than with consumer printers—there are many reasons for the low adoption of AM by industrial firms: production costs, material costs, throughput, lack of standards and certifications, etc.

Regardless, the bankruptcy of Desktop Metal—preceded by Nexa3D’s collapse and Velo3D’s last-second resurrection followed by a major restructuring—marks the end of the third era of additive manufacturing development.

Toward the Fourth Era…

Today, situation on the market is divided...

The consumer market is growing better than ever before. Dominated by Chinese companies—Bambu Lab, Creality, Elegoo, and others—it is breaking records in the number of 3D printers sold.

Visions developed in 2010–2012 by figures like Bre Pettis and Avi Reichental have finally become a reality.

However, desktop FFF 3D printers are ceasing to be part of “additive manufacturing” per se, and are entering a much more mainstream consumer electronics sector.

At the current pace of growth, it’s only a matter of 3–5 years before FFF 3D printers are seen in the same light as paper printers—becoming a standard part of the home tech ecosystem.

For industrial 3D printing, the situation will be different. The greatest need here is for better software, which must make designing metal 3D-printed parts much easier—and above all, more predictable.

Machine costs must decrease—while maintaining the same functionality. In other words, the same shift needs to happen that we saw in desktop 3D printers, where €2,000 is already considered expensive, and most prices hover below €1,000.

Materials must also become cheaper—and simultaneously obtain validation for use in selected verticals and applications.

Mass adoption of industrial 3D printers at the same scale as desktop FFF machines is unlikely—but increasing their share compared to current deployment levels seems rather obvious and inevitable.

Industrial 3D printers will simply not replace traditional manufacturing methods, but they will support them more extensively.

Either way, we are entering a new chapter in the industry’s development. Whatever happens next—it will be different from what came before...

#7. Andretti Global expanded partnership with Stratasys for 3D printing in INDYCAR

Andretti Global is deepening its collaboration with Stratasys to enhance technical processes in the INDYCAR series. Since 2018, Stratasys has supplied industrial printers, materials, and software, including Fortus 450mc and F370 systems. Key applications include rapid prototyping, functional parts, and tools like cooling covers, steering alignment brackets, and helmet vents.

READ MORE: www.3druck.com

#6. Ursa Major launched alliance to boost Additive Manufacturing for Defense

Ursa Major has formed the Alliance for the American Additive Manufacturing Ecosystem (AAAME) with partners like Dyndrite, EOS, and nLight to accelerate AM adoption for national security. The initiative aims to strengthen supply chains, standardize processes, and enable rapid production of defense systems.

READ MORE: www.voxelmatters.com

#5. Protolabs reported record revenue despite AM sector slowdown

Protolabs posted record Q2 2025 revenue of $135.1M (+7.5% YoY), driven by CNC machining (+20%) and supplier network growth (+19%). However, 3D printing revenue dipped 1% to $21.2M, reflecting broader challenges in additive manufacturing. While aerospace and medical sectors showed promise, injection molding declined 4% due to seasonal demand. CEO Suresh Krishna emphasized hybrid manufacturing growth but acknowledged margin pressures (44.8% gross margin, down YoY). The firm maintains profitability with $123M cash reserves and expects steady Q3 revenue of $130M-$138M.

READ MORE: www.3dprint.com

#4. 3D Systems launched FDA-cleared NextDent Jetted Denture solution in US

3D Systems has commercially launched its NextDent Jetted Denture Solution, featuring the NextDent 300 MultiJet 3D printer. The FDA-cleared system produces fully cured, monolithic dentures in one day—eliminating post-processing and manual teeth bonding. Compared to traditional methods, it cuts labor by 50% and reduces production time from five days to one.

READ MORE: www.voxelmatters.com

#3. Bambu Lab Launched Kickstarter-style crowdfunding platform for 3D printing projects

Bambu Lab has introduced a new crowdfunding feature on its MakerWorld platform, helping creators fund ambitious 3D printing projects. Backers can pledge money (minimum ~$10) to support campaigns, with funds collected only if goals are met—similar to Kickstarter. Rewards may include prints, digital files, or tutorials, but refunds aren’t guaranteed.

Currently invite-only, the platform already features a fully funded board game and other creative designs. Bambu Lab aims to foster innovation while managing risks through transparency and updates.

READ MORE: www.all3dp.com

#2. Anzu Partners completed acquisition of ExOne subsidiaries

Anzu Partners has received US court approval to acquire ExOne GmbH and ExOne KK following Desktop Metal's bankruptcy filing. The investment firm, which is also acquiring Voxeljet, pledged to maintain ExOne's operations, customer relationships, and service standards. Eric Bader (ExOne GmbH) and Ken Yokoyama (ExOne KK) will remain as Managing Directors. Anzu emphasized continuity in digital sand casting solutions, with Whitney Haring-Smith stating the firm's commitment to stability and trusted partnerships.

READ MORE: www.tctmagazine.com

#1. Desktop Metal files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, ending turbulent decade of operations

Desktop Metal has filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, marking the collapse of one of 3D printing's most prominent companies. The filing includes 15 subsidiaries, with assets/liabilities between $100M-$500M. Nano Dimension, forced to acquire DM in April 2025, seeks to sell international assets (ExOne, EnvisionTEC, Aidro) to Anzu Partners to reduce debt.

The bankruptcy concludes a contentious takeover saga involving lawsuits, regulatory battles, and $90M in disputed legal fees. Restructuring officer Andrew Hinkelman now oversees DM's uncertain future.

READ MORE: www.3dprintingjournal.com